ARTICLES

Saburo Murakami: Art that Gloriously Comes to Life in an Instant

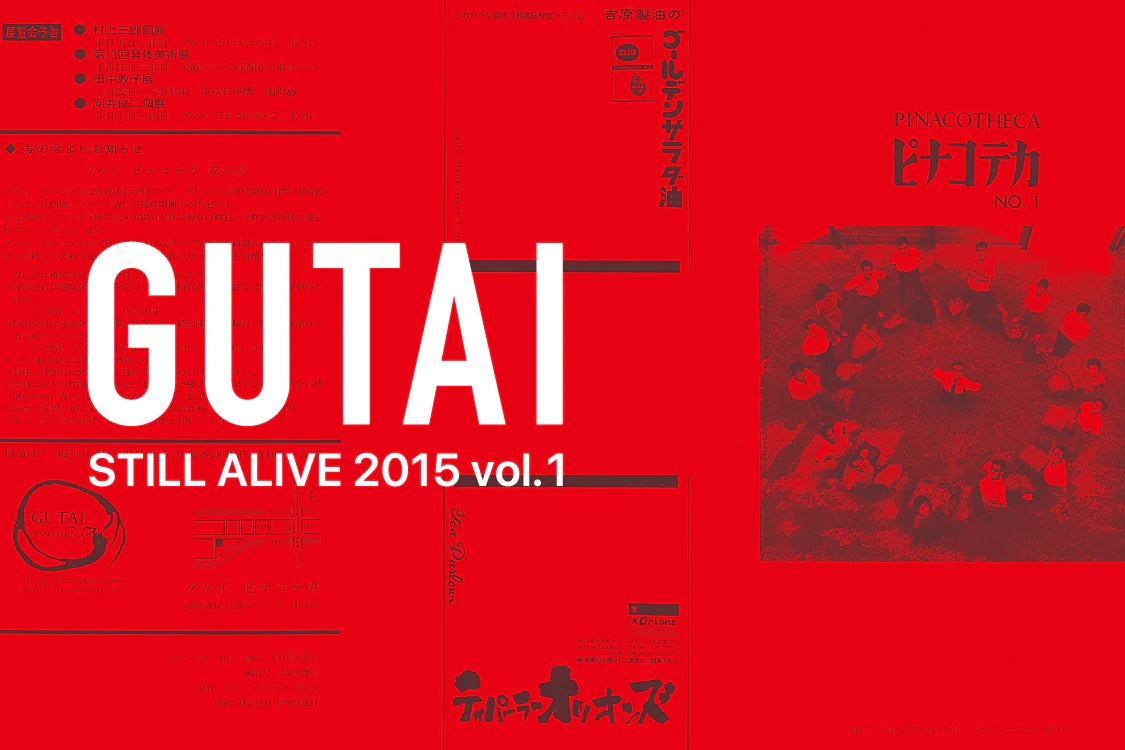

GUTAI STILL ALIVE 2015 vol.1

23/35

A project evolving the digitized archive of the book, “GUTAI STILL ALIVE 2015 vol.1”. The 23rd edition focuses on Saburo Murakami, a core member of Gutai best known for his "kami-yaburi" paper tearing performances. In this interview, we talked to Atsuo Yamamoto, a curator who had close ties with Murakami and who began his career in the Ashiya City Museum of Art and History.

Saburo Murakami: “Beauty” That Materializes Splendidly and Instantly

Atsuo Yamamoto Chief Curator, Yokoo Tadanori Museum of Contemporary Art

I still remember the moment I first met Saburo Murakami, with my boss. A novice in the profession, I was rather nervous because I had heard that Murakami was a “philosopher” or “theoretician” in the Gutai group. But Murakami was an unexpectedly soft person. With a friendly smile, he disarmed anyone instantly. “What’s your specialty?” – he asked me. “Well, I was an art history major, but I didn’t study hard … so I actually don’t know much about art … I’ll study from scratch,” I confessed. His reply was surprising: “That’s wonderful! It’s really nice to be able to see things without preconceptions.” I now realize that that was an extremely profound remark, but at that time it just made me relax. Thanks to that, however, I would say I have been able to keep working until today.

At the opening of a retrospective of Gutai (Penrose Institute, Tokyo, 1993), Murakami said, “Please stop calling me ‘sensei’ (doctor),” which I can’t forget also. All Gutai members had respective strong personalities and they sometimes conflicted between them. But Murakami was revered by everyone. I believe that that had something to do with his attitude of viewing things in the purest manner, without any prejudices (including someone’s title and age).

But there was a moment in which Murakami got incredibly stern. That was less than one hour before he talked to me at the above-mentioned opening. Murakami made the work “Entrance” at the gallery’s main entrance for an opening ceremony. The work had been originally made for the first Gutai exhibition (Ohara Kaikan, Tokyo, 1955). He shut up the entrance with a sheet of kraft and then Jiro Yoshihara tore it with the entire body, in what can be seen as a precursor of today’s “installation” or “performance.” The entire gallery, with its entrance shut up, became an echo chamber, and the space turned into a huge percussion instrument. The impact of that “sound” can’t be imagined from documentary pictures.

The sun had already set. The light seen through the tears of kraft, accompanied with the astounding sound of tearing, was beautiful. I was so moved that I ran up to Murakami to congratulate him but, against my expectation, he only gave me a side glance and no words. He later told me, “I don’t feel like talking after a performance,” but I got embarrassed by that, thinking I might have offended him some way.

What’s intriguing about “Entrance” was that it brought about a feeling that the world had changed completely after the performance. With the astounding sound Murakami moved from a space to a different one in an instant, and the two spaces became united. Murakami at that instant was like a chick coming out from an eggshell, just having been “reborn.”

I can’t describe it right but, for Murakami, artwork was very close to some kind of “leap.” For example, his remarks on “Please Walk on This,” a work for the viewer to experience by Shozo Shimamoto, were really unique: “What’s great about that work is that the work itself is in front of you, but its essence is over there” – then he pointed high above our heads. Working steadily and hard is of course worth respect. But apart from it, there is a kind of “beauty” that materializes in just an instant. Murakami’s aesthetics had something to do with such kind of dandyism.

I would like to write about Murakami’s paintings in the Gutai period, but the space here is too short. Since around the disbandment of Gutai in the 1970s, Murakami vigorously held interesting solo exhibitions. The paramount was “Mugon (silence)” (Mugensha, Osaka, 1973). Without a single word, it was an extreme example of the trend at that time to discard expression in the conventional sense. And in the ’80s Murakami ceased holding solo exhibitions.

Usually this might be regarded as a fade-out. His lifetime friend Sadamasa Motonaga said, “San-chan (Murakami’s nickname) had some very exciting plans. So I told him to write a book, but he never did. He was true Saboro (lazy boy, in Japanese).” But actually Murakami had never retired. To understand this, one should read “Two and a Half Drops of Bitters – Thus Spoke Saburo Murakami” (Seseragi Shuppan, 2012). It’s a record of Murakami’s sayings written by Tatsunori Sakaide, the master of Bar Metamorphose, where the artist frequented in his last years. The book vividly tells that Murakami was an artist who sought absolute freedom from any kind of systemization of art. To me, it’s a bible.

The life of Murakami was completed by three major works of paper tearing. The forenamed “Entrance” (1955); “Passage” (1956), in which he tore a total of 42 sheets of kraft stretched on 21 frames: and “Exit” (1994), where the artist went through a sheet of soft and thin paper to outdoors. More performances had been planned in a solo exhibition in 1996 at the Ashiya City Museum of Art & History (I was in charge of the exhibition), but Murakami suddenly passed away, three months before the opening. Many couldn’t help feeling that the artist’s “absence” was his last work.

(Mothly Gallery, July 2014)

Read more about the “Gutai Art Association »

*Information in this article is at the time of publication.